Scarecrow and the Sound of a Fractured America

Heartland Rock in the Age of Reagan: John Mellencamp, Part Two

If Uh-Huh marked the moment John Mellencamp began paying attention, 1985’s Scarecrow is where he stopped hedging. This was not simply an album about struggling farmers. It was a record shaped by the political atmosphere of mid-1980s America, a nation projecting confidence abroad while absorbing economic and cultural strain at home. Where Uh-Huh hinted at fracture, Scarecrow confronted it. In its anger and clarity, Heartland Rock ceased to be nostalgic and became political.

Scarecrow turned rural dispossession into chart-topping protest music, and it remains Mellencamp’s most uncompromising statement. It’s not merely an album about farmers; it’s an album about America in 1985, prosperous on the surface, anxious underneath.

What happened to American farmers in the early 1980s was not merely an agricultural story; it was an early warning signal. The same economic doctrine that promised renewal was producing uneven consequences: prosperity for some, precarity for others. As Reagan celebrated electoral landslides and Cold War resolve, rural America was confronting foreclosure auctions and collapsing banks. Scarecrow was born in that contradiction.

To blame Ronald Reagan as the sole reason the American farm system imploded in the 1980s would probably be incorrect. For an event as catastrophic as the farm crisis, there were several factors that played a role.

One thing that affected farmers was that Federal Chair Paul Volker sharply raised interest rates. This matters because farmers had borrowed heavily in the 1970s to purchase land and equipment. As a result of the rate hike, loan payments skyrocketed, which led to massive farm foreclosures. Additionally, land values collapsed, and families went bankrupt. Reagan matters here because he supported Volker’s action, despite its devastating impact on rural borrowers.

While Reagan’s economic policies led to a strong U.S. dollar, they reduced the competitiveness of U.S. agricultural exports. Not helping matters was the Soviet grain embargo, which was a holdover from former president Jimmy Carter, and exports dropped sharply in the early 80s.

During the peak crisis from 1981 to 1986, over 250,000 farms were lost, farm income fell by over 50%, land values dropped between 40-60% while rural agricultural banks were failing.

As a candidate, Reagan was the champion of the “free market” and promised Midwestern farmers that he would get the government out of agriculture. In fact, his stump speech said he would “make life in rural America prosperous again” and “restore profitability to agriculture.”

Many farmers embraced Reagan’s free-market rhetoric and grew crops to compete on the open market. And for many reasons, some of them detailed here, the market did not respond in kind.

Moreover, Reagan flatly refused to do what every previous administration had done: pay farmers to stop growing. U.S. farming had been underwritten by the government since FDR’s New Deal.

There is no denying Volker’s interest rate shock, some over-leveraging in the 70s, and a global commodity implosion played a role in the farm crisis; however, Reagan’s policies of tight money, reductions in farm support, and an overall belief in market discipline over protection worsened rural collapse.

For many in the Midwest, Ronald Reagan’s approach felt like abandonment.

ALBUM 2 OF 4 - SCARECROW

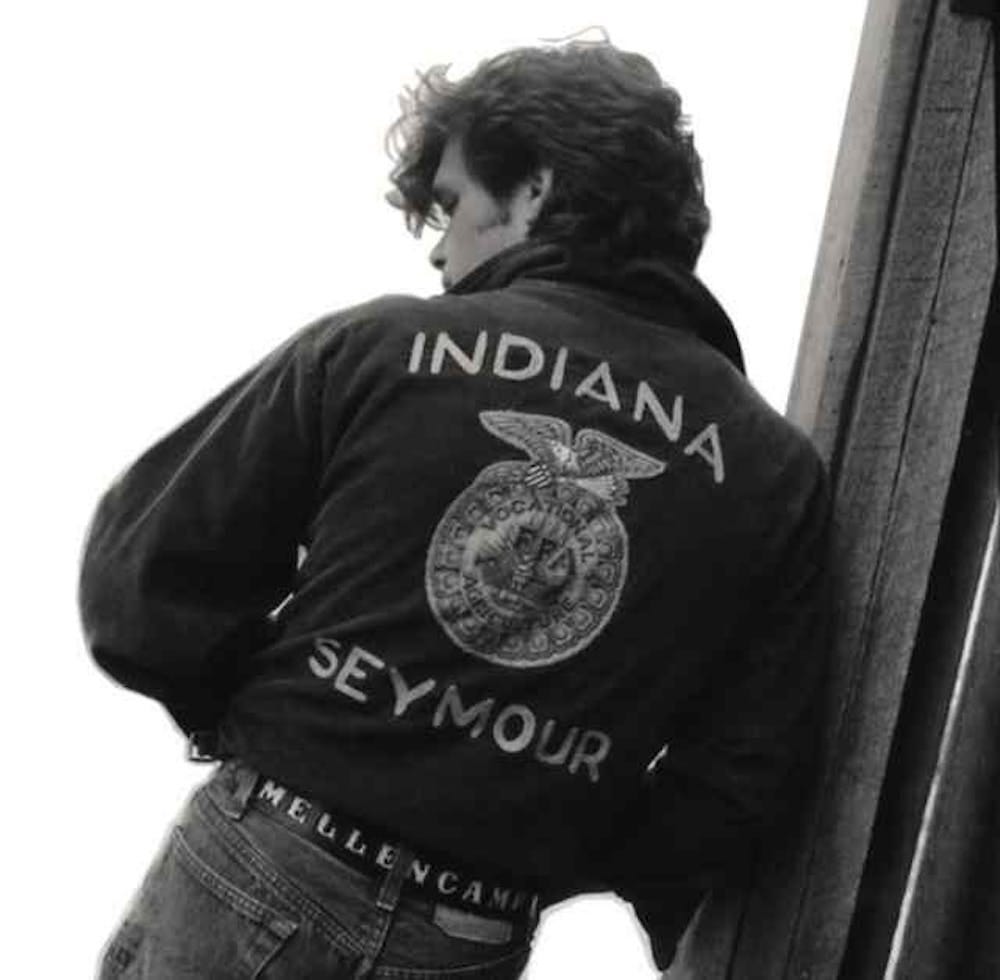

After a successful tour in support of the multi-platinum Uh-Huh, John Mellencamp returned home to Seymour, Indiana, to a rural community that was in crisis. American farmers were facing an economic crisis more severe than any since the Great Depression. In March of 1985, Mellencamp and co. stepped into his Belmont, Indiana, studio to lay down his thoughts.

Released in August of 1985, Scarecrow was Mellencamp’s eighth album and definitely his most politically charged to that point. He wastes no time in firing a shot across the bow with “Rain on the Scarecrow,” the first song:

The crops we grew last summer weren’t enough to pay the loans

Couldn’t buy the seed to plant this spring and the farmers bank foreclosed

Called my old friend Schepman up to auction off the land

He said John it’s just my job, I hope you understand

Calling it your job old hoss sure don’t make it right

But if you want me to, I’ll say a prayer for your soul tonight

And grandma’s on the front porch with a

Bible in her hand. Sometimes I hear her singing take me to the promised land

When you take away a man’s dignity he can’t work his fields and cows.

There’ll be blood on the scarecrow, blood on the plow.

As the fourth single, “Rain on the Scarecrow” details the emotional toll that government policy and farm foreclosures had on Midwestern farmers. The song is a narrative about generational loss, pride, and despair, all of which Mellencamp witnessed firsthand in Indiana.

The single, released in 1986, peaked at number 21 on the Billboard Hot 100. Not too shabby for a song with powerful social commentary on a topic as focused as the collapse of rural farming communities.

Five of Scarecrow’s eleven songs are politically charged. Almost a threefold increase from Uh-Huh’s two songs. The songs often paint a musical portrait of the struggles of various Midwestern characters. This isn’t just simple “Reagan sucks” type of music, it’s painting pictures of those feeling the wrath of Reagan’s policies.

The second song, the traditional “Grandma’s Theme” (sung by Mellencamp’s grandmother, Laura Mellencamp), can easily be seen as an allegory for the artist’s agenda:

Was a dark story night

As the train rattled on

All the passengers had gone to bed

Except a young man with a baby in his arms

Who sat there with a bowed-down head

The innocent one began crying just then

As though its poor heart would break

One angry man said “Make that child stop its noise

For it’s keeping all of us awake”

The image of sleeping passengers and a crying child echoes a nation ignoring its own distress, and resenting anyone who dares to make it audible.

While not overtly political, the fourth track sheds light on the things that make the Midwest so unique. Spanning three generations, it’s with “Minutes to Memories” that Mellencamp paints the values of Midwestern life in 4:11.

Like “Rain on the Scarecrow,” this track was co-written with Mellencamp’s childhood friend George M. Green, and stands as one of his most cinematic, reflective, and mature songs to date.

On a Greyhound thirty miles beyond Jamestown

He saw the sun set on the Tennessee line

He looked at the young man who was riding beside him

He said I’m old kind of worn out inside

I worked my whole life in the steel mills of Gary

And my father before me I helped build this land

Now I’m seventy-seven and with God as my witness

I earned every dollar that passed through my hands

My family and friends are the best thing I’ve known

Through the eye of the needle I’ll carry them home

As the old man shares his life’s wisdom with the “young man” who is presumably Mellencamp, much is learned about the core values of life.

He said an honest man’s pillow is his peace of mind

This world offers riches and riches will grow wings

I don’t take stock in those uncertain things

By the last verse, the young man of the bus ride has matured, realizing the old man was right. He lays down this wisdom for what is presumably another young person:

Days turn to minutes

And minutes to memories

Life sweeps away the dreams

That we have planned

You are young and you are the future

So suck it up and tough it out

And be the best you can

It’s worth remembering that by 1985, thanks to Reaganomics, income inequality had seen a sharp increase with more wealth concentration at the top. It’s against this backdrop that Mellencamp closes out side one of Scarecrow with “Face of the Nation”:

And the face of the nation

Keeps changin’ and changin’

The face of the nation

I don’t recognize it no more

By 1985, Ronald Regan had survived an assassination attempt and was being referred to as “the great communicator.” Riding high, it was true that the face of the nation had changed. And depending on your political or cultural beliefs, and your economic status, exactly how the face of your nation changed was different.

Reagan’s America looked triumphant on television. In rural counties, it looked different.

In 1985, the Cold War was not metaphorical. It was doctrine. Mutually Assured Destruction between the two superpowers, America and the USSR, wasn’t a slogan; it was policy.

“Justice and Independence ’85” distills Mellencamp’s view of America into three and a half pointed minutes, a civics lesson delivered with a snarl.

He was born on the fourth day of July

So his parents called him Independence Day

He married a girl named Justice

Who gave birth to a son called the Nation, then she walked away

Independence would daydream, and he’d pretend

That someday him and Justice and Nation would be together again

But Justice held up a shotgun shack, wouldn’t let nobody in

So Nation cried

Oh-oh when the Nation cries

His tears fall down like missiles from the skies

Justice, look into Independence’s eyes

Can you make everything alright?

And can you keep your Nation warm tonight?

Well, Nation grew up and got himself a big reputation

Couldn’t keep the boy at home no, no

He just kept running around and around and around

Independence and Justice, well they felt so ashamed

When the Nation fell down, they argued, “Who is to blame?”

And Nation, if you’ll just come home, we’ll have this family again

Not helping matters was a policy that became known as the Reagan Doctrine. This doctrine provided overt and covert aid to anti-communist resistance movements in an effort to counter Soviet-backed communist governments in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Under the banner of containing communism, American power expanded globally, even as economic strain deepened at home. This makes “Justice and Independence ‘85” one of Mellencamp’s most politically fueled songs up to that point.

The rest of Scarecrow is far from a throwaway and finds John Mellencamp in familiar territory and firing on all cylinders.

“Small Town” - “Pink Houses” part two with Mellencamp as protagonist

“Lonely Old Night” - small town boredom meets booty call (although allegedly inspired by the movie HUD… I remain skeptical).

“Between A Laugh and A Tear” - relationships (with Rickie Lee Jones on background vocals)

“Rumbleseat” - nostalgic reflection

“You’ve Gotta Stand For Somethin’” - some braggadiccio with some humor

“R.O.C.K. in the U.S.A.” - nostalgic reflection part two

FARM AID

As great an album as Scarecrow is, the album’s legacy is closely tied to one thing in particular: Farm Aid.

By 1985, musicians had gained an overwhelming degree of self-importance. The high-water mark of this era is the two Live Aid shows that took place in July of 1985. In an offhanded comment during Bob Dylan’s set, he mentioned that the organizers should give some of the money to the American farmer. Those organizers may not have been listening, but John Mellencamp, Neil Young, and Willie Nelson were.

Two months after Live Aid, on September 22, 1985, Farm Aid was born in Champaign, Illinois.

By all accounts, including the three founders, Farm Aid was conceived as a one-off project. Now, if you don’t think that some of Ronald Reagan’s policies had a lasting impact on farmers, in September of 2025, Farm Aid celebrated its 40th anniversary on September 20, at Huntington Bank Stadium in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

With Uh-Huh, Mellencamp was observing. He was taking notes, testing the temperature, hinting at a fracture.

With Scarecrow, he stopped hinting. He indicted.

He indicted economic doctrine. He indicted political indifference. He indicted a national mood that celebrated strength while ignoring strain.

Scarecrow captured a country split between confidence and collapse, a nation flexing abroad while foreclosing at home, projecting certainty while absorbing quiet despair.

Four decades later, that tension doesn’t feel archival. It feels familiar.

In part three, we’ll look at John Mellencamp’s The Lonesome Jubilee, which picks up where Scarecrow leaves off.

Well done. I've always felt Minutes to Memories and Between a Laugh and a Tear are two of Mellencamp's best deep cuts. A fantastic overall album.

Thank you for placing this album in a thick description of its socio-political context. You deftly capture its message in and to the crisis of its day. The album's message, unfortunately, is still relevant 40 some years after its debut. I'm enjoying this series.